“Where am I, or what? From what causes do I derive my existence, and to what condition shall I return? … I am confounded with all these questions, and begin to fancy myself in the most deplorable condition imaginable, environed with the deepest darkness, and utterly deprived of the use of every member and faculty. Most fortunately it happens, that since Reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, Nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation, and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends. And when, after three or four hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.”

― David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Hume was an Empiricist and declined to pursue a career in law, likely for the same reasons that, were he alive today, he would have avoided any kind of IT work, which is largely spent focusing on something imperceptible to the five senses (information) and drawing inferences purely from what is immaterial/non-physical. But such a frame of mind tends to follow a person beyond whatever workplace, and everyone is to some extent (for the most part intuitively/unconsciously, I think) trying to connect dots, align seemingly unrelated events, and compose a coherent picture of reality. That’s how our minds function, and so to dismiss all causal thinking due to the fallibility of sense perception, as Hume essentially did, is to consign oneself to a psychologically and emotionally crippling limbo. Life must make sense to be meaningfully lived. The above quote demonstrates that Hume both understood and was haunted by this truth. Why then would he choose to live in miserable “melancholy and delirium”? My theory is that Hume was not at all “confounded” by the weighty questions of existence but rather steadfastly avoiding conclusions to which reason would inevitably take him (or maybe just rejecting these conclusions outright because he could not accept what they implied).

For example–with respect to the potential causes from which Hume might have “derived his existence”–if we thoughtfully examine DNA, which is arguably the most complex and specified biological molecule that we know of, we can infer (through the non-physical means of mathematics/probability) that this 3-billion-symbol-long data structure encoding the instructions for synthesizing all the proteins necessary for life is demonstrably not the result of random unguided processes. Such a structure is necessarily engineered. A few more inferences then naturally follow: Where there’s engineering, there must be an engineer; since DNA is the building block of life, this engineer must necessarily transcend life; and since DNA is also information, which is free from the confines of Scientific Materialism, this engineer also transcends matter, energy, and space-time. Hume was unaware of DNA, but contemporary observations would also, at the very least, have pointed to a non-contingent “necessary” Being and otherwise inexplicable functional complexity in the natural world, just as they did for Aristotle some twenty-one centuries earlier, and Hume would have been disingenuous to deny that the description of a super-intelligent engineer who transcends life, matter, and energy evokes a Particular Person to mind.

Roger Scruton observed that a major endeavor of post-Enlightenment philosophy was to establish an objective moral framework without reference to that aforementioned Particular Person, to give “secular grounding to a shared moral position,” but you can see this endeavor already gaining some momentum in the Enlightenment with the likes of Hume. We can’t necessarily say that Hume was an atheist in the modern/post-modern sense of the word, but he was widely regarded as an atheist by 18th-Century standards. He also suffered a trauma common to the personal histories of almost all atheist/agnostic/skeptical people: a damaged, troubled, or non-existent relationship with his father. Hume’s father died when young David was just two years old, and his mother never remarried, raising Hume and his older brother as a single mother. The facts of Hume’s skepticism and his fatherless upbringing might seem unrelated, but psychologist Paul Vitz makes a convincing case that they are quite closely linked. In “Faith of the Fatherless: The Psychology of Atheism,” Dr. Vitz turns Ludwig Feuerbach’s “projection theory” of God–i.e., that God is essentially a creation of human consciousness as an outward projection of human nature–back on itself to implicate deficient or non-existent fathering as the primary cause of atheism. Rather than a mere projection of human nature or an intellectually principled belief/unbelief based on some sober examination of evidence, Vitz shows how our views of God appear to be mostly influenced by one major developmental factor: the relationships we have with our fathers.

Author John Eldridge calls this developmental deficit the “father wound,” the emotional/psychological (and spiritual) damage inflicted by a substandard or absent father. For good or ill, our relationships with our fathers shape our posture toward God, and whether or not we are inclined to religious belief is not a matter of some suppositious “God gene” but rather of developmental stages most influenced by whatever benevolent paternal influence we experienced. We are emotional, psychological, and spiritual beings as well as we are intellectual, and all these dimensions of our experience are relevant, though perhaps not equally so. One need not be an outright atheist with a fatherless upbringing to witness this developmental force at work. In my former agnostic life, I was often in conflict with my own father, to whose real or perceived disapproval I responded with frustration, which gave rise to anger and, ultimately, rebellion and alienation. This dynamic plagued our relationship from the time I was eight years old until I was well into my 30s, and it greatly prejudiced my view of God: If I was such a disappointment to my imperfect earthly father, how much more of a disappointment must I be to the perfect Creator of all things, seen and unseen?

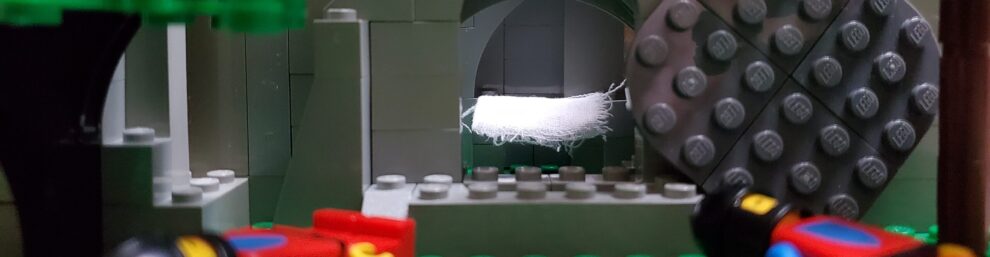

C.S. Lewis’ experience as an atheist was also consonant with the idea that we all have an a-priori concept of God: “I maintained that God did not exist. I was also very angry with God for not existing.” Vitz shows us that our concept of God is demonstrably presumptive, and given the inescapable evidence for God and the corresponding scientific/philosophical groundlessness of obstinate skepticism, any questions of His existence or presence are irrelevant. If we can be honest about that truth, we are then free to examine how accurate our pre-existing prerceptions of God the Father may be. I think Jesus often presented a picture of the Father not as wrathful, intransigent, and rejecting, but rather as merciful, solicitous, and compassionate because He knew that in reconciling our perception of God to what is true about Him, we might also find reconciliation in the broken relationships we despaired of ever healing.