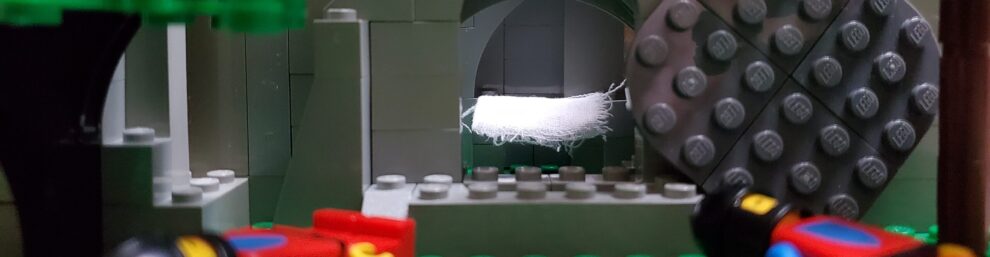

Just over two years ago my daughter was born six weeks premature at 3 pounds 13 ounces, which is why we sometimes affectionately call her “Peanut.” Like her brother, she’s precociously smart and mischievous. Unlike her brother, she was born with her eyes wide open: As we sang the Doxology and all eyes stared at us (“What are those weirdos singing?”), it surprised me to notice that one pair of eyes was my daughter’s. Most newborns don’t fully open their eyes for a few days, but Peanut came out of the gate looking at everything. When the staff moved her to an incubator and I went with them, a nurse told me that as long as I was going to be in the way I might as well shield Peanut’s peepers from the harsh light, so I did. I doubt she blinked once. Before my daughter’s personality began to emerge her eyes gave us clues. They’re happy, pensive and kind, and she communicates with them. I also think she sees things that most people don’t, and I won’t be surprised at all if she becomes an artist of some sort. She already shows an affinity for drawing and coloring (mostly on paper, fortunately, but sometimes on furniture, unfortunately).

It sounds crazy, but eight days after Peanut’s birth, a bunch of women were stomping around Washington, D.C. dressed up as female reproductive organs. As far as I can tell, these women were protesting what they perceived as an infringement of their civil rights, namely the alleged right of my wife to have killed my daughter if she were still in the womb. Ironically, one organizer of the mass vajayjay-stomp, Linda Sarsour, is a proponent of sharia law, the Islamic legal code that, where practiced, deprives women of their most basic rights, including the right to vote, hold public office, drive cars, be secure in their own persons and property, dress up like a giant hoo-ha, and so on and so forth. On YouTube, I saw a counter-protester at the March for Life “educating” pro-lifers on the finer scientific points of fetal ontogeny by screaming “It’s just a clump of cells!”–which is a claim that even honest pro-abortion advocates admit is scientifically untrue.

I thought a lot about what I desire most for my daughter, and while I’m still clarifying that, I do know for certain already that I want her to know the truth. Almost every other desire I have for my daughter could be subsumed in that because the truth will best guide the trajectory of her life. For example, I want her to have the moral courage to fight injustice, but I want her to know what injustice truly is rather than waste her time fighting ghosts. I want her to know that she’s beautiful based on a true concept of beauty rather than the objectifying “beauty” of our contemporary culture. I want her to know what love truly is: an arduous journey of dedicated work, humility, and self-sacrifice, not vacuous politeness, flattery and virtue signaling. I want her to know that, contrary to the reductive philosophy of the pu**y-hat mob, she is infintely more than a set of body parts and perceived grievances. I want her to know that she has–and has always had, even when she was an alleged “clump of cells”–the unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I want her to never settle for less than her full potential. I want her to know that she’s not the result of an accidental collision of amino acids that just happened to assemble themselves in a fictitious primordial soup. And I want her to know that she’s not a powerless victim adrift in a sea of randomness and evil, but rather that her life has inestimable meaning, purpose, and value because she was created by a sovereign God Who loves her, has a plan for her life, and truly empowers her.

The biggest obstacle I’ve encountered is that most people don’t want to know or seek the truth. By default, the truth is unpopular, especially today as the prevailing (and inherently contradictory) trend in western thought is that there is no “absolute” truth and that all truths are confined to their own particular social and historical contexts. But truth was no more esteemed nearly 2,000 years ago when the Roman prefect of Judea dismissively quipped “What is truth?” before turning Jesus over to the baying mob. The world demanded His brutal public execution because He told the unvarnished truth, but even pleasant truths are often rejected (just listen to my wife when I tell her how beautiful she is). We may praise truth passively, but we actively and tirelessly suppress it. And as Western civilization continues to decay, I’ve noticed a persistent refrain among its antagonists: Those who suffer due to their departure from the truth that makes civilization possible try to persuade everyone else about the validity of their perverse subjective morality, often when they clearly don’t believe in it themselves and even exploit the innocence of children in attempting to buttress their own tottering psychological defense mechanisms.

Supressing the truth is a tireless task because the truth is infinitely enduring (and if you’ve concluded that truth is ultimately an attribute of an infinitely enduring Person, as C.S. Lewis did, I would agree with you). Truth comes back to bless or haunt you, whether you like it or not. This happens on the individual as well as the societal level. Ravi Zacharias once posed this rhetorical question to a hypothetical multi-culturalist:

“In some cultures they love their neighbors, and in some cultures they eat their neighbors. Do you have a preference about what kind of culture you’d like to live in?”

His point was that cultural disagreements over morality aren’t proof that there is no objective moral truth because while different cultures disagree about what is right and wrong, civilizations must embrace some key common values simply to endure. For example, a culture that doesn’t promote courage is unlikely to produce a competent fire department. A culture that doesn’t value honesty isn’t going to have a sound economy, because we need to be able to trust each other to do business. A culture that doesn’t enforce equal justice under the law can’t expect citizens to respect the law. Such cultures are incompatible with civilization, and civilizations that embrace these cultures will certainly fail. Conversely, civilization can’t even begin without an incubation of compatible culture, which is why people living in uncivilized cultures tend not to have roads, writing, currency, etc. Everyone is too busy preparing for the next internecine conflict or otherwise coping with the chaos of their uncivilized world. This is true regardless of racial groups or geography, from the highlands of 20th-century New Guinea to the highlands of 17th-century Scotland. The extent to which we have a healthy civilization is in direct proportion to our embrace of objective moral truths that are congruent with human nature.

Another instance of objective moral truth is the inherent value of children, regardless of how their mothers (or the New York state legislature or Ralph Northam) may feel about them. The phrase “demography is destiny,” often attributed to the French agnostic philosopher Auguste Comte, is demonstrably true even to moral relativists, and if they take an honest look down the road of civilization, they can’t help but foresee the slow-motion collision between “choice” and demographic reality. But again, these collisions can be both societal and deeply personal. Agronomist Norman Borlaug, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work to end world hunger, had just died in 2009 when I heard a comedian joke on late-night TV, “I was hungry yesterday, so I made myself a sandwich. Where’s MY Nobel Prize?” Moral obtuseness makes for good comedy in the postmodern world, and after living and working in the eminently postmodern Boulder area for almost 20 years, I think I have some insight. People in Boulder County are famously solicitous about the welfare of prairie dogs–just read letters to the editor of the Boulder Daily Camera for a few years, and you’ll know what I mean–but they’re also very supportive of abortion, even late-term abortion. So what’s the particular social and historical context in which it’s okay to condone killing a child (and even hardened abortion advocates will admit it’s a child) but not okay to condone killing prairie dogs? To be blunt, the context is nothing more than narcissistic convenience. For the virtue-signaling activist, advocating for prairie dogs will earn the easy praise of bien-pensant progressive peers; but attending a prayer vigil outside an abortion clinic will get you cursed at, spat upon, and possibly even physically assaulted. Of the potential parent, prairie dogs ask nothing; but children demand constant care and attention lasting many years. Also, children are expensive to raise, feed, and educate; but selling their body parts might just earn you enough to buy a Lamborghini. That’s really all there is to it. When you look beyond the exhibitionistic moral preening and self-congratulatory bombast of the prairie-dog cult, you can see people simply saying, “I was hungry, so I made myself a sandwich. And I’m awesome, so where’s my Nobel Prize?”

But here’s a better quote about being hungry:

“I was hungry … and you gave me something to eat. I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink. I was a stranger and you invited me in. I needed clothes and you clothed me. I was sick and you looked after me. I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

Certainly not stand-up comedy, but when we learn what we’re truly here for, it’s what we’ll long to hear. It’s what will forever run through our minds whenever we have time alone to think about what really matters.

“I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat.”

“I was born six weeks premature, 3 pounds and 13 ounces, and you sang with joy over me.”

“I was colicky at 2 AM, and you paced the floor with me and kissed the tears off my face.”

“I pooped in the bath tub, I was artistic with the furniture, I was mischievous and inconvenient, but you were patient with me.”

“You loved me well. You showed me the Truth.”